Self

“How do we re-define ourselves before we have had a chance to define ourselves even a first time?” -Katie

When our world feels flipped upside-down and turned inside-out, we often have to negotiate existential questions. Who am I now? Who do I want to be? Here we describe how we stay true to ourselves and draw strength from within to adapt to our changing circumstances.

Whenever someone starts asking what's going on or asks what the story is,

there is a look of sheer shock and terror in their face as you explain what's happening.

I don’t know if I have ever really dealt with my prognosis.

I don’t really know what it is, as they don’t know so much about medulloblastoma in adults, and they just say they don’t know. But once you’ve been vulnerable, you always feel vulnerable.

If my past self could see my new self, I would be curious as to how I'm mentally able to cope with all this.

When you look back at what you were capable of before and what you're capable of now, and all the limitations let alone the possibility of imminent mortality it's a lot to take in. It's especially hard to take in at first.

The first time I was diagnosed, I made a conscious decision to stop letting cancer define me.

I learned how to take control and make cancer a part of me, as opposed to all of me. But it’s different now that I have terminal cancer. I feel like I have lost all sight of who I am because, at this stage, cancer touches every part of my life and has changed everything. It has control over my mobility, sexuality, spirituality, relationships, and finances. When I meet people, it’s so hard to answer the usual questions that I end up lying. I tell them what I used to do for work, or I answer “no, we haven’t had kids yet,” as if that is our choice. If I don’t lie, then everything ends up being 100% about the cancer.

My relationship with cancer remains unusual, I believe.

I share grief when I lose family, friends, and loved ones to cancer. But I feel uncomfortable when people say things like “I hate cancer.” Cancer doesn’t feel invasive to me. Genetically, it’s something that most of us are born with. It’s ancient and more ‘human’ than any illness. I take comfort in feeling that my cancer is a part of me, every bit as much as my voice, my eyes, or my hands. I’m perhaps overly stoic or philosophical about death. To me, the world is overpopulated as is — if cancer takes me, then maybe it means it’s part of my job to make space for someone new.

Initially, I was told 18 to 24 months was the median lifetime expectancy for my cancer.

But then I was also told, "we all have patients who live longer." Once I get to the 5-year mark, then I’ll go down to a 20% chance of having a longer life, so you see that dramatic drop; 80% of women with my cancer don't make it to 5 years. But, statistics aren't people.

Cancer has control of my death, but I don’t want it to control my life.

I don't want it to define me, but I’m not sure if that's even possible. Cancer is making all the important decisions for us. It has decided we can’t have children and that I can’t work. It changes how well I sleep, what I eat, what events I go to, my relationships with my family. It has changed everything about everything. I can’t distinguish between me and the cancer. Honestly, right now, I don’t know where cancer ends, and I begin.

The oncologist never gave me any stats on life expectancy.

It basically came to me looking up some of the typical stats. Even then, they are American ones. There are very little Canadian studies. I like to know what I'm up against. I understand that statistics are the past. They are not my future, but they are a representation of what people have dealt with so I can kind of get my head around questions such as "Is it more likely that I have a couple years or a couple months?." The stats I found was that the average life expectancy for Stage IV breast cancer was 33 months. That made sense to me because I had friends who were diagnosed and only lived a month or two afterward, and then others who were alive 7 years later. I have seen both sides of the coin. That is with me when I think of myself.

My doctor struggled to find the words to tell me all my chemo treatments had failed.

He was trying to say “we are between a rock and a hard place” but he just got to the word ‘rock’ and then was obviously flustered, desperately trying to remember the analogy… I finished the sentence for him, tried to give him strength with my body language, and didn’t dare to glance over at my mother who was sitting there with me. I knew what this meant, and in a way, I was prepared. It had been a long time coming, and that helped me stay calm in that particular moment… but about 2 minutes later the reality of it hit me. All of a sudden I was clambering to try to think of ways in which I could survive one moment, and asking my team what it would feel like to die the next moment. It was like a Pandora’s box of questions without answers.

There are all these cancer-related things that are not life or death, but affect you and affect you in a significant way.

I have Horner's syndrome, so one of the lymph nodes pushes against a nerve that controls my left eyelid which droops a little bit, and it doesn't dilate properly. It’s my face! Other people don't really notice it unless I point it out, but I notice.

One thing I really miss is nose hair because my nose runs all the time now.

People don't realize that when you lose your hair, you normally lose all your hair and that's why your nose is running 24/7.

My reconstruction surgery was important to give me a slight sense of normalcy when I looked in the mirror.

I wanted to have just that slight bit of normalcy and control in my life. That's all it was. After the reconstruction failed, my husband continues to say that it's for me to decide (about more reconstruction) and he supports me. For me, I want to go back to how I was before. It's also about being able to do small but essential things like wearing a shirt, without having one large side and one flat side, which stretches out my clothes and wears them down on one side but not the other.

When I look at myself, I see an extra 50 pounds that I have gained due to treatment, and inactivity due to feeling ill, fractures and general fatigue.

I see extra hair on my face from being in menopause by my late 20s. I see crooked teeth from the cancer in my jaw. I see scars. I see a face that looks like it's middle-aged even though I am only 33. I use a cane to help with mobility. I see bruises from medication that thins my blood...

Losing my hair was demoralizing.

Even before I lost it, I was so afraid to lose it. It happened three weeks into radiation. At one point I thought maybe I will be lucky and I won’t lose it, but I did, first a little, then a little more and then it just came out in clumps. My appearance changed so much – no hair and I went from 150 to 180 pounds because of the Dex. I felt like I lost my identity.

For about a month or a month and a half I walked around with my head down.

I felt so ashamed, and so unlovable. I felt so ugly. My girlfriend and my grandpa– they didn’t care about my looks. They saw me as the same person– but I didn’t feel like me. My hair is back now, and I am almost at my normal weight, but I have lost so much strength in the time I was first diagnosed till now, it feels like I'm a completely different person from pre-cancer me.

When it came to appearance, my hair used to be one of my big identifiers.

I always had long hair. It was even down to my belt the first time I lost my hair, and down to my bra line the second time. It would be great to have normalcy with that too. I have silly wigs now, electric blue, cotton candy pink... They are more for me to have fun with so if I wanted to I could wear one. You get so used to simple things like hair, and then suddenly it’s gone.

My voice isn't my voice anymore and that affects me a lot.

My voice! It’s my voice! ... c’mon ...even that!?! I often feel like I don't have control and so much of my identity is wrapped up in these things like how I hear myself, the ability to control the modulations of my voice, and what I look like in the mirror.

When someone sees me on the street, they have no idea I have cancer because I don’t look anything like what pop-culture thinks a cancer patient looks like.

I have short and wispy hair (not a bald head), strong filled-in eyebrows, and a puffed out face rather than a skinny one. I grieve the loss of my body, and not just in its ability to just “exist-without-pain” or “exist without-cancer”, but in this so-called ‘superficial’ way about appearance. The more I think about this, the more I think that we are told looks are ‘just superficial’ (and of course they totally are), but it’s becoming shockingly apparent just how much the people around me seem to value those things. And yet, even though when I go out in public, people stare and some look apprehensive when they see my wispy hair, giant bandages, and yellow-tinged skin, I've come to realize that when I smile and laugh people smile and laugh with me just as they always did. I guess it’s not an either/or situation. I’ve learned that it’s OK to look back on what I had and miss it, and at the same time, I truly am learning about the power and truth of inner-beauty.

I have seen lots of AYAs with cancer who are angry, and with good reason.

I have many friends who are angry about my diagnosis, but it’s not one of the feelings I hit on very often. I think for me, anger is such a wasted emotion. Whether I get angry about it or not, it's not going to change my diagnosis. It's something that just happened to me. I feel a lot of other emotions, but anger is just not one of them. It’s like being angry would be even more draining, and it’s already so draining to have cancer. If there was an outlet for the anger, maybe I would feel differently. But there is no one to blame, no one to specifically aim the anger toward. There’s no accountability to be assigned to someone. Cancer doesn’t discriminate. It’s just so random. It just happened.

What my husband and I do have, is a lot of sadness.

We laugh our way through just about everything – probably to save us from crying. But for us, it's just better to laugh than be angry and be fighting. It’s not easy, but it’s a conscious decision and choice for us.

If my past self could see my new self, I would be curious as to how I'm mentally able to cope with all this.

When you look back at what you were capable of before and what you're capable of now, and all the limitations, let alone the possibility of imminent mortality, it's a lot to take in. It's especially hard to take in at first.

The anniversary of the day I was diagnosed, March 11, is tough for me.

This year was 7 years. I absolutely hate that day. It's a day that nobody recognizes. It's not like I get many texts from people acknowledging it on that day. A few people know about it, but very few. It's a day I want to just get through. Near the end of 2017, I figured out that I didn’t want to deal with that day the same way that I've dealt with it for the last 6 years. I wanted to do something different. I'm always talking about how lucky I am in my life. I have so much, despite the Stage IV cancer. I really do have this amazing blessed life. So, I thought “I'm going to do 100 days of gratitude”. I counted back from March 11 and figured out that if I started on December 2nd, that would be 100 days out from March 11. I decided to start a Youtube channel, and I decided to do a video every day about something different that I'm grateful for in my life because I knew that would not be difficult. I knew I could easily come up with 100 different things. Every day I did a 5 to 10-minute video of something that I'm grateful for. It picked up a little steam, a few reporters found out about it, and there were stories written about it. I had a bit of a following. As time went by, I thought, “Hey, I kind of like this.” Then March 11th came and my 100th day was about my husband, and again that picked up a lot of kind of steam and March 11th was a lot easier to deal with. It totally worked. It did its job. What I wasn't prepared for was this immense amount of gratitude that I just had for life and that I REALLY realized that it's not about how much time we have. It's about how that time is spent. Quality over quantity. I just took a deep breath and thought, “Wow, that was a way bigger project than I had anticipated.” The effects of it were massive. And then I found out that the clinical trial treatment that I had been stable on for two and a half years stopped working. I went on another trial. My cancer progressed even more. Now I'm back on chemo. What I didn't know was that on March 12th, my friends and family got together and started 100 days of Katie. They had connected with each other without me knowing. There were 100 different videos about how people were grateful for me, and what they were grateful for in their life. It was just so contagious that every day I got a new video from somebody in my life. That knocked my socks off! And then in the middle of that, it was my 34th birthday. Birthdays are such a massively big deal for me. I wasn't sure I was going to make my 32nd birthday and now we're at my 34th. So I decided to do another 100 days, to end on my birthday. This time it’s going to be 100 random acts of kindness. So many people have done so much for me. I knew I was going into chemo and I wanted to remind myself every day what amazing people I have in my life. And I wanted it to be a part of my legacy. Anybody who has a friend with cancer and doesn’t know what to do will now have 100 videos and 100 things that people have done for me that they can now reference and do for their friends. I'm on day 88 today of 100 things that people have done for me. I could come up with 1000 things.

I think my biggest coping strategy is to try to release some of that trash talk that we are all so good at.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) has really helped me. When I'm being really hard on myself and talking that horrible self-talk, I imagine picking up the phone and calling one of my girlfriends. If she told me how she was feeling and what she was going through, I wouldn't shit on her. I wouldn’t say, "You should be walking more, and who cares if you have two fractures in your pelvis," and "Get those teeth fixed" and all the terrible things that I would be saying to myself. I would say, "You have Stage IV cancer. Your body is doing everything in its power to try to heal itself, to try to deal with the treatments, to try to handle the cancer. You woke up and got out of bed today. That is a victory.” I imagine myself being with one of the many people in my life and having them talk me “off the ledge” by reminding me of how crazy my life is, and that these physical things are a side effect of this bullshit that I'm going through.

Going for walks outside, especially long rambling ones is one thing that really helps me.

I used to be a runner but I can't run right now because of the pain in my bones. But I can walk. By walking I can still have that experience of seeing the city at a human pace. By walking, you experience the slow changes of a place and your relationship with what's there changes. That's been incredibly important to me.

One of my main ways of coping is that I have a psychiatrist.

For a few years I even had two psychiatrists, because my primary psychiatrist wasn't able to see me more often than once a month, so she found me a second psychiatrist who could see me weekly. I've visited a psychiatrist for years, since shortly after my de novo diagnosis, because I've wanted to talk to someone who wasn't my husband. I talk to him about everything, and he is my primary support, but I didn’t want to put everything on him. I wanted to have a space where I could get it out and cry about it and share my darkest fears without hurting the person who was listening. It's hard with family, to have them not take on related pain when you're showing the true depths of your pain. Very few people have seen me letting the depths of my pain show.

There is often a fine line between tragedy and comedy, so I spend my days making jokes, bad jokes, any kinds of jokes.

I’ll laugh with myself, my parents, my friends, and my health care professionals. In more serious times, I use a meditation technique that has yet to fail me. I breathe out “blackness” and negativity and breathe in a “lightness,” joy, hope, and strength. This helps me process what’s stressing me out and hurting me at any given point, but to let go of the bad. It has also helped me tap into my sources of strength, take moments to be grateful for what I have. Most of all humour and meditation give me a sense of control.

Because I'm alone so much, we're in the process of getting a puppy!

I'm really excited. That way I won't actually be alone. I'll have someone following me from room to room and that will be great. Animals give a pure love that's so nurturing...

Advice from Health Care Providers

Self and identity

“Who am I now?” is a common question that young adults living with advanced illness ask themselves. How you answer it is up to you, because nobody else has a right to define who you are. You might find that you are also changing your definitions of other things, like “what success looks like” or “what I truly value.” Maybe “success” means getting out of bed and doing one thing with your day. What you “value” might be the important people and relationships in your life.

After everything you’ve been through, you might feel like a different person than you were before. How could something so significant not be life-changing in some way? Your own self-identity has likely evolved in one way or another. There may be a part of you longing for things to go back to how they were before. Maybe you have experienced changes to your body as a result of surgery or treatment. Adjusting to these changes is difficult. There may be another part of you that likes the person that you have become. There may be yet another part that feels confused and lost in this whole process. It’s entirely possible that you are feeling all of these things at different times, or even at the same time!

You might be struggling with self-esteem and body image. Adolescents and young adults with advanced illness can feel so much pressure to feel positive (from others and yourself) that sometimes it feels wrong to feel down or upset. It is perfectly understandable (and expected) to have shitty days. You don’t want every day to be like that, but humans aren’t supposed to be super positive all of the time. Try to be patient and compassionate towards yourself.

There are likely parts of your identity from pre-diagnosis that you want to carry with you as you move forward. There may also be parts of yourself or certain relationships and values that you want to leave behind. That’s OK. It’s your choice and a very personal decision.

You might find that others have labels for you like “warrior,” “fighter,” “survivor,” “hero,” “brave,” or “courageous.” If these make sense and fit for you, that’s great, but you might find these labels either don’t fit or are actually unhelpful to you. There is no right or wrong, and while some find these helpful, others find other ways to describe themselves. You might reject all labels because nothing can capture all the complex things that make-up who you are.

Figuring out who you are now, and who you want to be, takes time. It is not a one-time event, and it is part of being human to change and develop over time and with different life experiences. There is, however, that inner core of you that is always with you and always will be.

Resources

- Canadian Virtual Hospice

- Young Adult Cancer Canada

- Localife

- Survive and Thrive

- On the Tip of the Toes

- StupidCancer

- Lacuna Loft

- LIVESTRONG: Adolescents & Young Adults

- National Cancer Institute

- CanTeen

- LiveWire

- Teenage Cancer Trust

- Teenagers and Young Adults with Cancer

- YouCan Ireland

- This Should Not Be Happening: Young Adults With Cancer

- In-Between Days: A Memoir About Living with Cancer

- When Breath Becomes Air

- The Bright Hour: A Memoir of Living and Dying

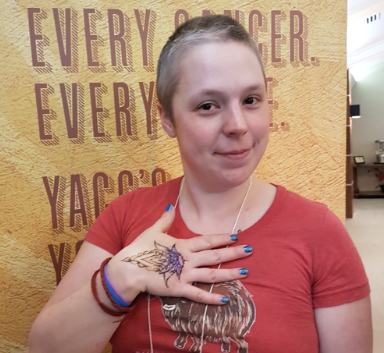

Katie Davidson

I was 26 when I was diagnosed, and like lots of people that age, I was still trying to figure out who I was.

I see on websites and hear professionals say that when you are diagnosed with cancer, you need to find your “new normal” or “you have to redefine yourself.” I just keep thinking and saying how crazy that is when you are diagnosed so young – hell, we haven’t had a chance to figure out who we are, period. How do we re-define ourselves before we had a chance to define ourselves even a first time?

Katie Davidson

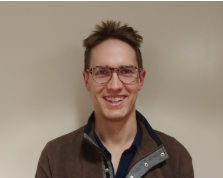

I'm three decades away from the age most people are when they are diagnosed, and I was 8 years too old to be considered pediatric.

People just can’t comprehend it. It's like "Wait, you shouldn't have cancer." It doesn’t compute. It just doesn't make sense.