Relationships

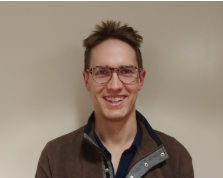

“I had not, in 5 years, met another single cancer survivor in my age group. I felt extremely isolated and felt that this was a need to be filled.” -Matt

Living with advanced illness affects how we connect with family, friends and our broader communities. What we say to each other matters, and maintaining and nurturing relationships takes time and work. We talk here about figuring out how to stay authentic and connected to others. We also discuss our often complex relationship with our health care teams.

A good friend is someone who listens,

and who understands that cancer is and will always be part of my life now.

Most of my friends haven’t been able to relate.

They don’t know what to say or how to be, or they don’t want to believe it. They just kind of “brush it off”. They’re great if I need distraction or basically to have someone to play with, but they just don’t get it. The people who do get it are the ones I met through Young Adult Cancer Canada (YACC) and the “Retreat Yourself” I went to in 2019, and if you can, go to one. It’s one of the highlights of my life.

Luckily, I have friends who say things to me,

like "You brushed your teeth today? Have a little party for yourself! That's a really big day!"

I'm finding that people are now more ready to accept and share their love.

Friends who maybe wouldn't have said that they love me before, say it now. I'm really grateful for the way they show their love in action, by giving me a hand when I need one.

I had not in 5 years met another single cancer survivor in my age group.

I felt extremely isolated and felt that this was a need to be filled. That need was filled by Young Adult Cancer Canada (YACC) (and later, in a smaller way, by the Brain Tumour Foundation of Canada.) I participated in YACC’s “Retreat Yourself” weekend that summer, and it was a life-changer. I truly connected for the first time. I felt that I belonged and was understood, and I feel that I made friends for life. This has been re-established each year through YACC’s annual conferences and through its social media presence.

Sometimes it's the last person you ever thought would leave you, someone you thought had your back no matter what,

and all of a sudden they are cutting you out, they are laying blame on you, engage in shaming and things like that. For some people it's defense, they are scared of cancer, scared of death, and they pull away from anything and everything about it even though they know it's not contagious. It's total self-preservation - when you hear something bad or something dangerous you pull away from it. Other people are assholes and you don't find out until push comes to shove. I've seen friends who have lost their spouses and significant others. When you start delving into it you find out that they weren't in the best of places before, and cancer was that extra wedge that led them to separate. And then you turn around and there are some people you hadn't previously thought of very often, and they show up with casseroles at the door, watch the kids so you can nap, drive you to appointments, or check in with you to see how you are doing and offer to take you out for a treat if you need it.

I have a really good community and I think that's a good place to be in when you're coming into a thing like this.

Still, it's hard to know how to build that up for people who don't have it. I think that's one of the great things about this project; it builds ways for people to connect.

I'm part of a couple of Facebook groups, some of them are for metastatic patients,

some of them are for young adults that have breast cancer, some of them are for parents who have cancer. None of them are directly relevant to my exact situation as a stage-four breast cancer young adult with children, but I have a variety of online groups to draw from.

Most of the new friends I made when I was first diagnosed have died.

We talk about that statistic of 5-year survival for my type of cancer (20%). Our group started as five ladies who had the same disease and they are all gone now. I'm the only one left. Friendships that initially grow out of needing support, needing one another, can turn out to be something that causes us pain and “survivor's guilt” and all of those things. We have to find ways to reconcile those things.

I'm the youngest of three, and I am definitely the baby of the family!

It’s hard to give parents bad news. As we grow up, our parents shield us from the information and situations that they perceive we can't handle. I find that I am shielding my parents from my metastatic cancer diagnosis in the same way. My parents aren’t able to come to many appointments because they live hours away. They’re relatively young too. They are not at retirement age. That gives me a little bit of control over when and how much information I want to tell them. I don't keep anything from them, but in the same way that they protected me when I was a child, I find I try to protect them from every detail of their "baby's" terminal cancer.

I didn’t have a great childhood.

I didn’t grow up with loving parents. It became too toxic so I moved in with my grandparents when I was 15. When I was diagnosed, I thought this would change our relationship for the better, but it didn’t. My grandpa on the other hand truly stepped up to help in whatever way he could. He doesn’t understand everything I am going through, but I know he is in my corner and I feel unconditionally loved by him.

I think my parents are still hopeful for a cure.

It’s very hard for my parents to talk about. Their youngest is dying. When I want to talk to them about dying and death, there is a lot of awkward silence.

I'm in a weird position.

The sicker I feel, and the more care I receive, the more independent I want to be. I feel very lucky. My parents help me out with laundry, food, and rides to the hospital, but they've supported my choice for me to live in my own apartment. They understand that I need to live my own life, no matter how redefined it is right now, and help without overstepping any boundaries. I'm so grateful for them. One of my 'cancer friends' is alone in his apartment, with no external support, while I have another one who is in high school and living with her parents. I know I'm incredibly lucky to be in the situation I'm in. Being grateful for these things helps me get through the days and redefine what a successful life means to me.

My husband is part of every decision that we make.

And it’s incredible how often and how many decisions we have to make. Every week it's a new "Do you want to go this route or this route?” Or, “This hasn't happened so we have to guess this is going to happen, and take this step." And I do not make a decision without him. And not because I don't trust myself. I often say "our diagnosis," "we have cancer,” "we have appointments tomorrow." It’s always “we” and “us” and “our.”

When I was diagnosed and through my treatment, my girlfriend was my main support.

My girlfriend and I broke up a couple of months ago. That’s been hard, but I am OK. She was an amazing support to me through this. There was a time I felt so ugly and unlovable – especially when I had lost my hair and put on weight with the steroids (part of my treatment). I needed constant affection and reassurance, and she was always there to support and encourage me when I needed that reassurance and confidence boost.

We're a military family.

I think that kind of helps us, because we know how to treasure the time we do have together because my husband can often be gone for a while if he has to go overseas, as opposed to a couple who knows they will be able to see each other every day. The fact of the matter is that we both love being with each other. We are best friends that are married. We do so many things together. We go to conventions together, and when we go to conventions together we dress up together. Last year we were Centaurs. This year we are hoping to go as characters from a webcomic that we read.

Talking about it makes it real.

This is actually happening. It was incredibly hard, but I'm happy we talked about the “what ifs” and “whens”. And my husband is too, but I think we're probably the only two who have really accepted that I will die of this. When there isn't that acceptance of what’s really happening, it’s really tough. What my husband and I do have, is a lot of sadness. We laugh our way through just about everything – probably to save us from crying. But for us, it's just better to laugh than be angry and be fighting. It’s not easy, but it’s a conscious decision and choice for us.

My boyfriend is there for me every day.

We spend time together as though I’m not sick even though I can barely leave the couch, need help up the stairs, as well as to get in and out of bed. People call him my “white knight” but I worry about him. He seems to be in denial about the gravity of my illness, and the more my health deteriorates the stronger his denial seems to be. I don’t want to press the point, but every time we talk about prognosis he acts as though everything is going to be fine. All I know is that I don't want my boyfriend to walk into my bedroom to find me dead one day, and I don't want to die without knowing he'll be OK.

We're a family that has little kids at home, so it's a lot to take in at first.

You want to and expect to be able to raise your children and all of a sudden you may not get to raise them, and you have to get used to the fact that somebody else might be raising your kids after you go. Depending on how things are, it could even be somebody you've never met before. So it gives you a bit of fear. You want to see your children grow up and you always have an idea in your head of the kind of future adults you'd like to shape and mould. There are things that you want for your children, things you want to teach them, freedoms you want to give them. Or freedom you wished you had in your childhood that you want to bestow onto your children. And then somebody else might have a different idea of how they are going to help raise your children, what they should become, or what they should do. You are thinking one way, and then realizing "this can all change."

My life expectancy was 33 months.

When I heard that, I started calculating what the state of my life would be if I made it that far. It would be that my daughter would not have started school yet, my youngest would not have had his third birthday yet, and my oldest would not have even approached junior high. It was slightly depressing to think about, but at the same time, I'm trying to be realistic about it. Not everybody gets a long life, and everything can change at the drop of a hat. As I kept having good responses with chemo, I knew I had a good chance of beating the odds, and I have because my son is now 3 years old. He's over 36 months, which means I'm past 33 months!

We fall through the cracks a lot because even among doctors the expectations of someone who looks generally well, who is generally well, is that they don't have cancer.

I applied for the Early Detection Program because I have a pretty strong family history, but I was denied because I didn’t have anyone who was first-generation, even though several close family members had cancer and all of my family’s cancer diagnoses were when we were young - in our thirties. But I knew to watch for it and I knew to be careful. When I was diagnosed with Stage IV, I was told, “We were looking for horses, but you were a zebra. You look like a horse, you sound like a horse, but you’re not a horse.” So they didn’t necessarily know the right thing to do.

For me, a good oncologist is someone who gives me full disclosure about what's going on.

I want to know exactly what the risks are versus the benefits. I want to know that I can trust what they say. I want to know that they will listen to me; that they will actually hear me out when I have questions about something. I want them to pay attention, and I want to to be able to tell that they are actually paying attention and not thinking about something else.

I had a doctor's appointment today for cannabinoids and she said, "How have you been feeling?"

It was a doctor I had never spoken to before. And I said, "Well, I have Stage IV cancer, I have a blood clot, I just had a blood transfusion, I'm on metabolic chemo." And she said, "Oh! You look good!" I get that all the time. I want people to understand that I might look good, but I feel like shit. And now they’re making me feel like I have to justify that I have cancer. I know it doesn't make sense to them, but it's the reality.

We did a lot of research, and we knew people who knew people and this oncologist kept coming up in our conversations who fit the description of what I felt I needed.

We emailed the oncologist directly and he wrote right back and quite quickly I started treatment. Access to a high level of care is not something that everyone has in Canada and that's kind of devastating. We live in a country that's so far flung and we have so many rural communities. You can't really run everything out of these small centres, but it means patients are missing out.

I'm probably the only young adult that my home care nurses see on a regular basis.

They come to my house 3 times a day, and some of them talk to me as though I'm in pre-school, and unable to look after myself. I'm an adult, not a child. I'm sick, not stupid. My body is weak, but my spirit is strong.

When I was first diagnosed, I was diagnosed in a different hospital than I am in now.

It was a smaller centre, and they didn’t have any oncologists on staff. A surgical oncologist called me and told me, “You have cancer, it’s Stage III. We’re going to do chemo, then surgery, then radiation, and soon you’ll be on the other side of this.” He told me, “This is going to be your worst day.” And I believed him. But then, when I got called back ten days later only to hear “We’re no longer looking for a cure,” that was the worst day. It really was the worst day. It was devastating. I was crushed. To me, it’s incredibly irresponsible that he gave me a diagnosis before all the information was in. It affected my trust, and that’s why I decided I didn’t want to be treated at that hospital.

The nurses are so wonderful here.

They are so capable and I barely ever feel a needle go in! These are things that I care about. Things like kindness. Simple kindness.

The quality I value most in an oncologist is someone who is straightforward, who tells me the facts directly.

It's someone who doesn't sugar coat anything, but also doesn't have to power over things. I also like humour. I don't like to break down around people, so I don't want someone who would be giving me "sad eyes.”

I need support from people.

If you are afraid of saying the wrong thing, tell me that. Saying nothing is not the right thing to do. I have enough obstacles in my life right now, I can't manage you turning away from me too. Never say, "If you need anything, let me know." Instead say, "What can I do for you?" Don’t leave it up to the person who is sick to have to reach out to you if they need help. Think about your strengths and offer that. If you're a massage therapist, offer a massage. If you can clean a house, offer to clean a bathroom. If you can price match, offer to save someone $20 on groceries. If you can drive, offer to drive to the hospital. Offer to pay for a prescription. Any of these things. Speak to your strengths and work from there. That is what’s going to be most helpful. The practical things that have helped me are when people say, "I'm at the grocery store, do you need anything?" The amount of energy that it takes me now to get into the car, drive to the grocery store, grocery shop, and drive back home is overwhelming. It’s a huge day for me. If somebody says,"What do you need?" and I rhyme off three things, it's so helpful. I've had friends stay for the weekend and then clean my toilets. It’s hard. It's so hard accepting that help. It’s impossible to ask for the help but when the help is just offered, it makes it easier. I don't want to need somebody to clean my toilets, but I do need it. I do need the help. After my surgery, my mom was in my kitchen on her hands and knees scrubbing my floors. I've had people prepay for reflexology appointments, which I find very helpful. Because of my fractures in my hips, I could not sleep, and I've had somebody get me a mattress foam topper to make my bed more comfortable. Flowers are incredible and when people buy nice things for me, that's lovely too. But I would take the practical stuff over and over and over again. Help with the things I'm going to have to do regardless. Anything that just helps me day to day. If they can cross that off my plate for me, that is such a huge help.

Advice from Health Care Providers

Relationships with others

Many people do not associate teens and young adults with advanced illness (and how wrong they are!). In fact, many people have a very limited understanding of advanced illnesses in general. This lack of knowledge can create situations where it is difficult for others to even recognize or acknowledge what you are experiencing. Even when other people do begin to see what you are going through, sometimes they express fear or denial which prevents you from getting the understanding and support you need and deserve. Fear and denial are powerful emotions. Some people may feel fear around you because they don’t know what to say or they don’t know how to best support you. It’s understandable that they could be worried about what will happen to you. Others might be afraid of illness and want to distance themselves from it (which obviously distances them from you too). People may express denial because they simply can’t cope with the facts. They might also be denying the reality that they could get sick someday as well. Let’s get one thing straight – you are not responsible for the fear and denial that other people are experiencing. You may be experiencing a lot of these same emotions and you should be allowed to focus on self-care and dealing with your own stuff. It is often hurtful when people react with fear and denial. Hopefully, your family and friends can come to terms with their emotions and support you in meaningful ways. If you feel comfortable, sharing your story with them might reduce some of the fear and denial. This may make things easier for you. That being said, it’s not your responsibility to soothe their fears. All this fear and denial can really cause people to say unhelpful things, even when they mean well. Anyone from your closest loved ones to strangers might think they need to say something to you. “But you’re so young!,” “I’m sure you’ll beat this!,” “All you need to do is think positive!,” “I know what you are going through...,” “Don’t give up!”… Where do people come up with this stuff?! There is a big taboo around advanced illness and death in our society, so this can lead to many awkward and hurtful conversations. You can choose how to react each time, whether it be ignoring them, explaining to them what you are going through or just going along with it because you want the conversation to end. It’s up to you, but try to respond in a way that meets your needs.

Relationships with friends

The impact of your illness on your relationships with friends might be one of the most concerning issues that you are facing. It can feel super isolating to be dealing with illness when your friends are not experiencing the same thing. Some of your friends might distance themselves, either on purpose or without thinking about it. They might be uncomfortable around illness and are not sure what to say, so they stop reaching out. This can be hurtful because it cuts you off from people you thought would be there for you in a time of need. You might feel that you get labeled as the “sick friend,” which is a crappy label to give to someone. You might also be the first one in your peer group to deal with something like this and some of your friends may have no idea how to react or support you (which is less likely to be the case for a group of friends who are a few decades older). Your friends might also say “tell me if you need anything,” which is well-meaning but is usually not helpful because it requires an extra step to reach out to them and ask for help. If you are feeling you don’t have enough friend supports, it can be difficult to make new friends at this point in your life as well. Other people may be uncomfortable around illness or your health prevents you from fully participating in the same activities as your peers. If you’re getting treatment, you are probably not seeing many other young people while you are there. All of this is happening at a stage in life when teens and young adults want to be more independent from their parents and caregivers, and peer relationships are becoming more and more important. There may be people who reach out to you who you didn’t expect and that can be meaningful. In other cases, you might want to be left alone and some people can be so persistent that it becomes aggravating! Or maybe you feel like YOU are the one supporting THEM. It’s a cliché, but some teens and young adults say that this is a time of “finding out who your real closest friends are.” Even if you do have supportive friends, it is still possible to feel isolated throughout all of this because it can seem that no one else really “gets it.” So what can you do about it? For starters, it’s ok to become more selective about who you spend time with. Some people may still be your friends, but you don’t need to spend your time with people that leave you feeling annoyed or drained. You also don’t need to be anyone else’s personal counselor. Try setting healthy boundaries and investing in relationships that make you feel good. Social isolation is so common for young adults living with advanced illness, but there are some great resources out there that you can connect to.

The power of community

Teens and young adults, when diagnosed with cancer, are hit smack in the face by an overwhelming feeling of isolation. It is wonderful to have the support of friends and family, but nothing really compares to being supported by people who truly get it. Finding someone who can truly relate to what you are going through and being accepted for who you are and how you are feeling without judgment is often a bridge out of isolation. Participating in digital and face-to-face programs with other adolescents and young adults often leads to not only a sense of community, but also a sense of safety, relatedness, and support. Young Adults Cancer Canada (YACC) is one organization that connects young adults with each other so they feel supported and understood on a deep level by their peers. The YACC community is diverse, from newly diagnosed, to living with terminal cancer. The richness that comes from connection and peer support is invaluable and the entire team at YACC is committed to taking care of this community, listening to its needs and making it grow. No young adults should have to deal with cancer alone and YACC has their back, always.

Relationships with parents

Your diagnosis might have impacted your relationship with your parents or caregivers. It may have had a negative or positive impact or no impact at all. This often depends on what your relationship was like before getting sick – have you been pretty open with your parents in the past? Do you feel emotionally close to them? It’s also possible that you had little or no relationship with them before getting sick, or one or both of your parents has already died, which can make things even more difficult. For many teens and young adults, living with advanced illness can be a threat to independence. You might have to move back in with your parents (if this is even an option), you might have to delay moving out for the first time, or you might find that your parents start showing up at your place WAY too often. In some ways, this might feel like “forced” dependence. It can be extra difficult to accept when you see other friends moving out on their own and living independently. Even with the threat to independence, it’s possible that your parents are your biggest supports. Maybe they help you out emotionally, physically or financially, depending on your circumstances. On the other hand, maybe your parents are getting a bit older and you are helping them with their health needs on top of dealing with your own! Or maybe you have your own young children and you are part of the “sandwich generation”. This “sandwich” is not as delicious as it sounds because you are caught in the middle caring for your parents, your children and yourself. Parents and caregivers can react in tons of different ways. Understandably, they might be worried about you. They might be highly anxious or “helicopter” parents. They might be distant or estranged. They might look to you for their emotional support, which is not your responsibility to provide. Or they might respect your autonomy and provide support when needed. You know your parents the best, so it’s up to you how you want to navigate these relationships while protecting your independence, privacy, and individuality.

Loss of independence

Many teens and young adults fear losing independence and becoming a burden on family members or friends as their cancer progresses. Some move back in with their parents for additional support. Others may live independently, but their parents have a larger role in the young adult’s medical care, including making medical decisions or basic care such as dressing or bathing. This loss of hard-won independence may be difficult for some to contemplate and accept. Young adults in serious relationships may fear changes in the dynamic of the relationship, shifting from being equal partners to being dependent on another individual for daily needs as well as emotional support. It is important to remember that the people surrounding you are willing and able to help. They likely also feel a sense of helplessness in this situation. It is okay to accept help and form new relationships with people that may be able to provide additional support to you and your loved ones (parents, spouses, significant others). There may be other people that are unable or unwilling to be a part of your life as it is changing due to illness. Ongoing, open discussions with others are essential to maintaining your personal identity, even as some of your independence may be reduced. Tell your loved ones what your personal needs are, from physical needs such as bathing and transferring to emotional needs like empathetic listening and venting. Be clear with others and set boundaries in terms of what help you are and are not willing to accept from certain people. Utilize available resources to ensure all your needs are being met. This might be a health care aide for personal hygiene needs, a psychologist or social worker to discuss your emotional concerns and needs, or a chaplain to discuss your spiritual questions.

Resources

- Young Adult Cancer Canada

- Localife

- Survive and Thrive

- On the Tip of the Toes

- KidsGrief

- StupidCancer

- Lacuna Loft

- LIVESTRONG: Adolescents & Young Adults

- National Cancer Institute

- CanTeen

- LiveWire

- Teenage Cancer Trust

- Teenagers and Young Adults with Cancer

- YouCan Ireland

- This Should Not Be Happening: Young Adults With Cancer

- In-Between Days: A Memoir About Living with Cancer

- When Breath Becomes Air

- The Bright Hour: A Memoir of Living and Dying

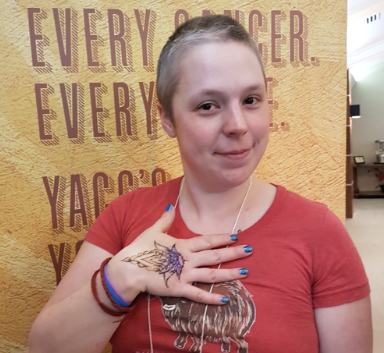

Katie Davidson

I am not “brave” for having cancer.

I'm just trying not to die. Odds are good you would do the same thing.

Katie Davidson

I made it very clear in the beginning that I am not in a fight with cancer.

I won't lose any battles, and I'm not a warrior. People who are living with advanced cancer are so fucking tired of listening to this garbage. It puts so much pressure on us when we have no control over it. If cancer was a battle, I would have won by now. I have cancer. Treatment either works, or it doesn't. I already carry so much guilt around about having cancer being the reason my young husband will be a widower and my parents will bury their youngest, and my friends will have this needless experience of grief. The thought that it is from “not fighting hard enough” is just too much to handle.

Katie Davidson

I didn't ask to get cancer.

I want the treatment to work more than anything, but the cancer cells dividing in my body right now are not saying to themselves, “She’s a warrior, so we'd better slow down.” It makes zero sense. I am such a positive person and I do absolutely everything I can. If I am supposed to do X, Y, and Z, I'll do X, Y, and Z and A, B, C to try to prevent the cancer from spreading. I will do absolutely everything not to die! I'm still not “fighting” cancer. The treatment either works or it doesn't.

Katie Davidson

People keep saying “You look good!”

I feel very sick on the inside, regardless of how you think I look on the outside. Just because you don't think I look sick, doesn't mean I'm not.